Thomas Shapter of Exeter

Abstract

Thomas Shapter spent almost all his working life in Exeter, Devon. He lived to be 93 years old. He is remembered primarily for his book describing the 1832 epidemic of cholera in Exeter in which 402 people died.

Early life and return to Exeter

The Shapter family’s forebears from Cornwall had settled in Devon in the mid-18th century (Image 1).

Thomas Shapter (Image 1) was born in 1809 in Gibraltar, where his parents were stationed. His father (also named Thomas) was born in Topsham, Exeter’s port, in 1769 and had a long army career. He was Paymaster of the 57th Regiment of Foot when he retired to Exeter. He married Mary Harrison (from Knaresborough in Yorkshire) in 1801 in Trinidad and the couple had four other children who survived to adulthood; John Shapter became a barrister and later a QC in London, and Henry Dwyer Shapter, after first training as a solicitor, graduated from Oxford and was appointed Perpetual Curate of Dowland in Devon in 1858. Their sisters Margaret and Mary never married.

Thomas Shapter was educated in Exeter. He gained some clinical experience in the Exeter Dispensary – a charitable hospital with a large out-patient clinic – before studying medicine at Edinburgh University. There he and his contemporary Charles Darwin (1809–1882) were Members of the Plinian Society, a club for members with an interest in natural history. By the time he graduated in 1831 Shapter had also studied in London, Dublin and Paris. His MD Dissertation was on old age, ‘De Senectute’.2

Soon after qualifying, he returned to Exeter where his parents were living. At that time, the city’s population was just over 32,000. He took over the High Street consulting room originally belonging to Edward Collins MD, a physician at both the Devon and Exeter Hospital and the Exeter Dispensary. In 1830 Dr Collins resigned and died the following year. Collins’s successor at the Dispensary was a 28-year-old doctor from Ireland, Peter Hennis (1802–1833).

Shapter and Hennis became friends. Both were involved in the 1832 cholera outbreak in Exeter but their friendship was to be short-lived.

In May 1833, recently knighted Sir John William Jeffcott (1796–1837), Chief Justice in Sierra Leone, was passing through Exeter. Jeffcott made some disparaging remarks about Hennis which he refused to retract.

Hennis challenged Jeffcott to a pistol duel3 which took place at a racecourse on the outskirts of Exeter. Before Hennis could fire, Jeffcott shot him, the bullet lodging in his left lung. Hennis was taken to his lodgings in Exeter where he was attended by several doctors, including Shapter, but died of his wounds eight days later, having forgiven his assailant. The post-mortem was conducted by the same doctors who had treated him. Shapter took home and analysed a piece of stone that was mysteriously found in Hennis’s chest close to the bullet and showed it to be of the same composition as other stone at the racecourse.

Hennis’s death led to a hurriedly advertised vacancy for a Physician to the Dispensary. Thomas Shapter’s application was dated 20 May, three days before Hennis was buried.

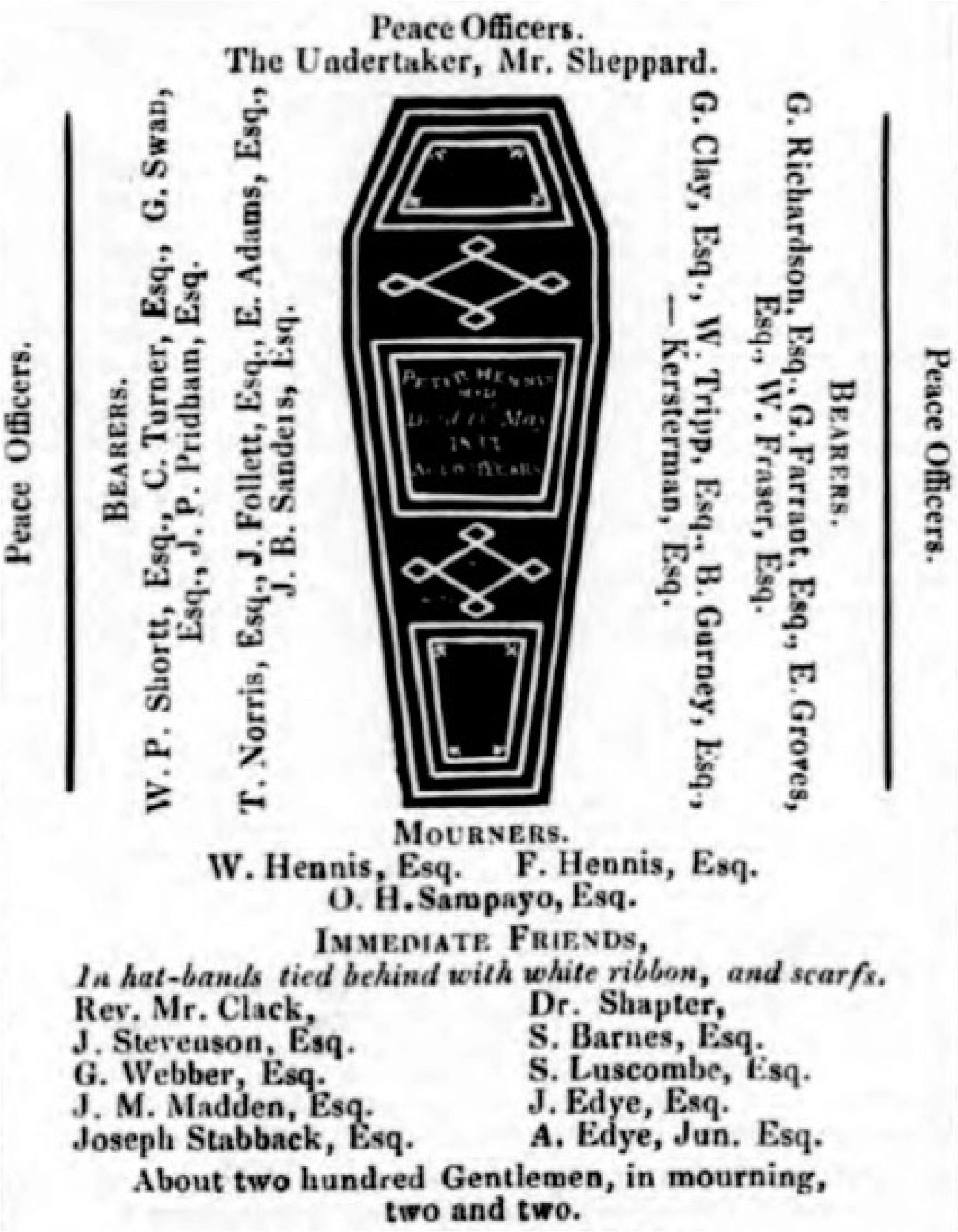

Shapter led a procession of 200 mourners through the city, past thousands of onlookers, to the funeral service and burial at St Sidwell’s Church (Figure 1).

At the committee meeting at the Guildhall to elect Hennis’s successor, Henry Blackall (1770–1845), the Mayor, proposed Shapter (who in due course was to marry Blackall’s niece). He pointed out that Shapter had been educated in Exeter. A more experienced doctor – Edward MacGowan – had also applied. The benefactors and subscribers voted for Shapter. (Benefactors were those who had donated more than ten guineas: Thomas Shapter’s father was the single most generous donor to the dispensary, having donated more than £30 in 1829.) The Dispensary position was honorary, and he was required to be ‘on duty’ one day a week.

Shortly afterwards he was also appointed Physician to the Lying-in Charity and became a Committee Member of the Exeter Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge.

In November 1833, his uncle William Randle Shapter died in Bath. Born in Exeter in 1766, after serving as an apothecary’s apprentice, he joined the North British Dragoons as a surgeon in 1788. He graduated MD from Glasgow University in 1792 and rose to be Inspector-General of Military Hospitals. He remained a bachelor. His body was brought back to Exeter for burial. In his will, he left all his properties in Cornwall and Essex to his brother, Thomas’s father.

Civic leader and author

As a ‘substantial and discreet citizen’, Thomas Shapter was appointed to Exeter’s Common Council (governing body) and was a frequent participant at society balls, usually accompanied by his sister.

In 1834 he was appointed a Commissioner of Improvement for Exeter. In that year he published ‘Medica Sacra or, Short Expositions of the more important Diseases mentioned in the Sacred [i.e. biblical] Writings’.5 He dedicated this book to John Blackall MD (a brother of Exeter’s Mayor and who for over forty years was a physician at the Devon and Exeter Hospital, and whom he would later succeed). However, the book received rather unflattering reviews, one suggesting he had plagiarised an earlier text.6

His privately circulated booklet, ‘A few observations on the Leprosy of the Middle Ages’7 was published in 1835.

Thomas Shapter’s father died in Exeter in 1838 aged 69, after ‘a long and severe illness’. He left his son Thomas the sum of £6,842 (equivalent to about half a million pounds today), and his estate in Ilsington, Devon.

In about 1840 Dr Shapter moved into his newly built mansion at Barnfield Crescent, close to the Devon and Exeter Hospital (Image 2).

Shapter contributed several chapters on specific fevers to ‘A System of Practical Medicine’,8 edited by Alexander Tweedie, and published in 1840. His articles were mainly reviews of the medical literature.

Around this time, he had sat for a portrait by John Prescott Knight RA (1803–1881). This was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1848 and donated to the Devon and Exeter Hospital by his son, Dr Lewis Shapter, in 1882 (Image 3).

Shapter married Elizabeth Blackall on 15 October 1840 in North Cadbury, Somerset. Born in 1814 she was the only daughter of Reverend Samuel Blackall (1770–1842).9

The 1841 England census shows them living at his Barnfield house with his sister Mary and four female and two male servants. Their near neighbours include former Mayor William Kennaway, and two eminent surgeons: John Haddy James (1788–1869) and Elizabeth’s second cousin, Samuel Barnes (1784–1858).

Children of Thomas and Elizabeth Shapter

All were born at their Barnfield Crescent home.

Elizabeth, born in 1841, survived only two days.

Elizabeth (1843–1892) married William Livesay MD; they settled in Sudbury, Derbyshire where he practised for 40 years.

Thomas Blackall (1844–1891) went to New Zealand in 1862. There he married music teacher Catherine Bunny in a Catholic ceremony; her father was a fraudster who had emigrated to the colony to escape his creditors. Thomas Blackall Shapter was a solicitor. After an unspecified scandal in 1875 they suddenly moved to San Francisco. He died in the USA.

Esther Margaret (1845–?) became a Catholic nun in the Order of Poor Clares.

William (1847–1929) joined his older brother in New Zealand in 1866. He returned to Britain and after training at Stonyhurst in Lancashire, he was ordained a Jesuit Priest in 1878. For several years he taught in Bombay. In 1907 he was a priest in Bury St Edmunds, Suffolk.

Lewis Henry (1848–1890) studied medicine at Cambridge, obtained an MD and later practised as a physician in Exeter, taking over many of his father’s appointments. In 1842 Thomas Shapter was appointed medical referee for the Medical Invalid & General Life Office. His brother John was their legal adviser.

Public health

Shapter’s earlier pamphlet on leprosy was republished as a book in 1842.10 He wrote ‘The Climate of the South of Devon’11 which twenty years later ran to a second edition.12 This marked a change of emphasis towards a study of epidemiology and public health. The book contained a wealth of statistical data on mortality rates (obtained by assiduously examining church registers), local geology and meteorological data, as well as a description of the major towns and their health advantages.

In 1843 he was appointed Vice President of the West of England Fire and Life Insurance Company. In August that year he gave the ‘Retrospective Address’13 in Leeds at the Annual Meeting of the Provincial Medical and Surgical Association. He discussed in detail the medical advances made over the previous twelve months based on his reading of the British and European literature.

He wrote ‘Remarks on the Mortality of Exeter’14 in 1844. This was an open letter to the Mayor, published as a booklet. He pointed out that while Exeter’s mortality rate was slightly lower than comparable UK towns, it was much greater than that of the surrounding rural areas of Devon.

He speculated that lack of ventilation, overcrowding and squalor were to blame.

He described the poorer parts of Exeter where he had witnessed ‘families consisting of eight, ten, or more persons, having but the limited accommodation of a single room ranging from ten to fourteen feet square, by nine feet high, in which they sleep by night, huddled together on beds and on the floor…’ and where ‘…more inconvenience is suffered from the keeping of pigs and the presence of slaughter-houses’.

He wrote a report on Exeter to the Health of Towns Association in 1845.15 This Association led to the creation of the Public Health Act (1848). At a public meeting in Exeter in 1846, Shapter described how for want of a drain costing ten shillings outside a house, twelve people who lived there were taken ill with fever. Three died. In addition to funding their medical treatment, the parish had to give financial support to the widows and children.

In the following year he was appointed Physician to St Thomas Lunatic Asylum in Exeter on the retirement of Dr John Blackall.

In 1847 he described a local outbreak of scurvy,16 describing the clinical features and (correctly) associating it with the failure of the potato crop. (In the workhouses, rice had been substituted for potato in the inmates’ diet because of the shortage of supply.)

On 4 November 1847 he was appointed Physician at the Devon and Exeter Hospital, again succeeding John Blackall. Other candidates withdrew their applications when they were aware that he had applied.

Later that month he was unexpectedly elected Mayor of Exeter – the previous nominee having declined the position. Most mornings he was required to sit as magistrate in the Guildhall. In September 1848 he resigned from the Dispensary.

Towards the end of his year as Mayor he had to quell a riot around St Sidwell’s Church caused by a clergyman giving a sermon while wearing a surplice: this signified a High Church tendency that was locally unpopular.

His book on the 1832 Exeter cholera outbreak17 was published in July 1849, coinciding with a large national outbreak which reached Exeter in Mid-August.

On 30 August 1849 his wife Elizabeth, aged 35, died of ‘inflammation of the lungs’, leaving him – with help from his sisters – to bring up five children between one and seven years old.

By 1852 Shapter had an electric telegraph installed in his house. In 1854 he took out a long-term lease on a plot of land on the Northern outskirts of Exeter where he built a house which he named Cobham and which he referred to as his cottage. In reality this had six bedrooms, an ornate garden with specimen sub-tropical plants18 and a resident gardener.

That year he and his family temporarily stopped attending his parish church (St Sidwell’s) as the new curate had ‘papish tendencies’.

In 1855 he resigned as magistrate and became President of the Southwestern District Branch of the Provincial Medical and Surgical Association, the forerunner of the British Medical Association.

Lunacy controversies

Mr and Mrs Lyon

The year 1859 was not a good year for Shapter. In February, the case of Mallalue v Lyon was heard in the Court of the Queen’s Bench. David Lyon, Deputy Lieutenant of Sussex, whose fortune derived from slave-run Jamaican sugar plantations, was being sued by the proprietor of a ladies’ outfitters for his wife’s unpaid bills of £362. Lyon’s wife Blanche (the daughter of Lady Charlotte Bury) had become addicted to stimulants and opium, prescribed after two miscarriages. Shapter, who already knew David Lyon socially, testified that in May 1853 Mr Lyon brought his wife to Exeter and arranged for him to meet her while the couple were dining in a hotel in the city. He certified her as ‘not in a fit state to have control of herself’ and as a result she was confined at a private asylum in Torquay, where he continued to care for her. Her condition improved and in September he deemed her to have recovered. At the end of September Mrs Lyon, now declared sane, obtained from the Courts a ‘deed for the restitution of conjugal rights’ and therefore the judge ruled that thereafter her husband was liable for her debts. The problem for Shapter was that David Lyon had written to him while his wife was confined in the asylum, insisting that he would only apply for her to be certified sane, and discharged, if she agreed to sign a deed of separation.

Phoebe Ewings and her will

In 1859 Miss Phoebe Ewings was about 80 years old. Although born in Feniton, Devon, where her grandfather had been vicar, for many years she had lived with her mother and sister in Warrington, Cheshire. After their mother’s death, the sisters occasionally returned to Exeter for several months at a time, where Phoebe and her sister had become friends of the Shapter family.

After her sister died in 1853, Phoebe started behaving strangely and wandering the streets in Warrington. She had no living close relatives. In October 1858 she had a small stroke, and temporarily lost her ability to speak. Her mental state deteriorated and she experienced paranoid delusions. At the end of December, she was confined in an asylum in Lancashire. Two months later she was deemed to have recovered. Shapter was informed, and contacted his friend, Revd Henry Ellacombe in Devon – who believed himself to be next of kin although they had never met – who collected her from the asylum and brought her by train to lodgings in Exeter. Shapter agreed to assess her and later stated ‘I thought she was quite capable of signing any document properly explained to her, and that I should have no hesitation in witnessing it’.

In April, a distant cousin, and her actual next of kin, Dr Henry Greenup of Farnworth, Cheshire, came to see Miss Ewings in Exeter. Believing her to be incapable of managing her affairs, he petitioned the Lord Chancellor for an enquiry into her state of mind. Although opposed by Shapter, the request was allowed. Dr John Charles Bucknill19 was commissioned to report on her mental state. He assessed her eight times between 6 and 21 June, mainly at her lodgings.

Meanwhile Miss Ewings appointed Dr Shapter as her guardian. On 30 May Shapter hand-wrote her will which she signed. He claimed that Miss Ewings had insisted, against his better judgment, that he would be both executor and the main beneficiary (of about £13,000).

On 2 July, part way through the investigation, Shapter arranged a second, almost identical, will for her to sign, this time prepared by Thomas Gray, a solicitor, and treasurer of the Exeter Lunatic Asylum. He later testified that this second will again made Shapter residual legatee, but the names of Shapter’s children had been added in case he should die in Miss Ewing’s lifetime.

An Inquisition in Lunacy was held by Samuel Warren QC in the Court at the Castle in Exeter over five days from 12 August. Thirty-three witnesses were called including twelve doctors. Bucknill’s opinion was that she was not capable of managing her affairs. Shapter confirmed to Bucknill that he was the major beneficiary of her will but added that he ‘wished some alteration to be made for my own sake’. Shapter was questioned for over three hours and at one stage was told by the Commissioner to ‘be calm’. He maintained she was sane.

In the afternoon of the last day the Commissioner interviewed Miss Ewings privately in front of the jurors. During this interview she offered to make the Commissioner her residual legatee. The jury took less than ten minutes to find her insane (and therefore not capable of making a will). Bucknill published a transcript20 of the inquiry without any comment.

Although Shapter consistently claimed that he would have declined the legacy, he came under criticism by The Lancet,21 for having arranged for the wills to be drawn up while he knew there was an ongoing enquiry into her mental state and, more important, that in his evidence to the enquiry he had not mentioned that his children’s names had been added as beneficiaries to the second will. Thomas Shapter was the subject of an investigation by the Royal College of Physicians as a result of his involvement with Miss Ewings’s will but no action was taken.22

The local press reported:23

The great Shapter scandal of the maniac’s will is still a subject of talk. The friends of the doctor have ceased to speak of it as an ‘indiscretion,’ and are now obliged to admit either a stronger term to characterize it, or to be altogether silent on the subject.

Miss Fewings remained in Exeter where she died, intestate, the following April after another stroke.

Ironically, shortly after the Ewings case, in December 1859 both Shapter and Bucknill were elected Fellows of the Royal College of Physicians of London.

In 1859 Shapter was appointed Chairman of the Exeter Water Company. He had been a shareholder in the company since its formation in 1833. He claimed to keep goldfish at his home in a vase containing the Company’s tap-water, to test the wholesomeness of the supply.

In February 1860 he was unanimously appointed as Consulting Physician to the Devon and Exeter Female Penitentiary, again in place of John Blackall who had died.

All three of his sons were educated – from as young as 13 – at the prestigious Westminster School in London. In 1862 his eldest son Thomas while a pupil there, converted to Catholicism at the nearby Brompton Oratory. News of this scandal was suppressed in the London newspapers but was covered in the Irish press.24 He was instantly sent home to Exeter by train, accompanied by one of the schoolmasters. Later that year this son went to New Zealand; his younger brother William (who later became a Jesuit) following him as soon as he was old enough.

Reverend and Mrs Lowe

In September 1870, Shapter was consulted by Mrs Louisa Lowe, 50-year-old wife of the Vicar of Upottery, in Devon. She had separated from her husband and was staying in Exeter. Revd George Lowe had arranged for Shapter and his friend Arthur Kempe, an Exeter surgeon, to assess her and certify her as insane; her husband then applied for her to be admitted to an asylum. Shapter was acquainted with the Lowes and especially George Lowe’s father, the Right Revd Thomas Hill Lowe DD, who was Dean of Exeter from 1839 until his death in 1861, and who had been President of both the Devon and Exeter Hospital and the Exeter Dispensary. Mrs Lowe was detained in several asylums, including that of Dr Henry Maudsley (1835–1915), for a total of fifteen months before being declared sane. She was convinced that her belief in spiritualism was the reason that she was classed as insane. She later formed the Lunacy Law Reform Association, of which she was Honorary Secretary, and unsuccessfully sued the Commissioners in Lunacy.25

In June 1877 Mrs Lowe and Shapter separately gave evidence to a House of Commons Select Committee on Lunacy Laws.26 In 1883 she wrote a book highlighting the unfairness of these laws,27 relating her experience28 and criticising Shapter as ‘renowned in lunacy official annals for ignorance of lunacy diagnosis’ – referring to the Ewings case.

In 1872 Lewis Shapter, his youngest son, qualified from Cambridge University, and almost immediately was appointed Physician to both the Exeter Dispensary and the Devon and Exeter Hospital.

Between 1866 and 1871 Shapter had written a series of papers for the British Medical Journal, titled ‘Notes and Observations on Diseases of The Heart and Lungs’. The articles were mainly about the physical signs of heart disease, and formed the basis of a book published in 1874.29

In 1875 Thomas Shapter was awarded an Honorary LLD by Edinburgh University.

Stepping down

In March 1876 he resigned as physician to the Asylum in Exeter. His son Lewis took his place.

In 1877 he unsuccessfully tried to stop a Coroner’s Inquest into the sudden death of one of his patients.

The year 1880 reports him pleading guilty to refusing to pay the sixpence toll for his coach and horse going to his ‘cottage’. The case was heard, in his absence, in the Guildhall where for so many years he had sat as magistrate.

He retired from clinical practice and within a few years left Exeter. He lived in St Albans and then for ten years in Forest Row, East Grinstead, Sussex with Ann Ferrett (who was his housekeeper-companion while in Exeter). They then moved into central London. (In 1890 he did return to Exeter when his 42-year-old son Lewis was dying from pulmonary tuberculosis. Lewis’s wife Charlotte née Bayly had died two years previously. Their five orphaned children were brought up by friends.)

On 29 November 1902 Thomas Shapter died at his lodgings in Earl’s Court in London. He left most of his estate to his son-in-law William Livesay. His eyesight had gradually deteriorated; poignantly, he was only able to sign his will with a mark. He was buried at Highgate Cemetery, in the family grave of his brother John.

Thomas Shapter had a fortunate start to his career as a doctor in Exeter. When, newly qualified, he arrived in the city, he was already well known. His parents were wealthy; he had benefitted from a classical education and his uncle was one of the most senior military doctors in the country. He was also clearly enthusiastic and clever. His MD degree – although a primary qualification – probably impressed. He slotted into upper class life. He was active during the 1832 cholera outbreak without having a specific role.

It is unclear why, as a relatively inexperienced 24-year-old, he already had such a high profile when Hennis died but this certainly put him in the limelight for filling the resulting vacancy at the Dispensary. He married into another wealthy family with local connections – the Blackalls, descended from Reverend Offspring Blackall who was Bishop of Exeter between 1708 and 1715. Of his father-in-law’s brothers, Henry was three times Mayor of Exeter and John was a Senior Physician at both the Devon and Exeter Hospital and the Dispensary. John Blackall was married to Laura, the sister of Samuel Barnes, Shapter’s neighbour and a surgeon at the same hospital. Shapter’s epidemiological writings stand out. Most of his other publications were about diseases and the physical signs that might lead to a clinical diagnosis. Although this was at a time when significant advances in treatment were being made, he rarely ventured into discussing therapeutics. Where he ran into legal problems with his psychiatric patients, a common factor was that they were women, and that he knew and had been influenced by their families. In attempting to resolve a difficult situation, in so doing he overlooked the needs and rights of his patient. He lacked insight into the stupidity of assisting Miss Ewings to sign a will leaving him almost all her estate.

He was widowed at the age of 40, and out-lived five of his six children. He did not seem to have close relationships with them. Two of his sons, having converted to Catholicism, went to live in New Zealand as soon as they left school. A mystery remains as to why he should have severed all ties with Exeter in the early 1880s.

Exeter in the time of cholera

Shapter’s famous book, ‘The History of the Cholera in Exeter in 1832’,16 was written 17 years after the epidemic. He dedicated it to his next-door neighbour, William Kennaway, who was Mayor of Exeter during the outbreak. Prophetically a contemporary national newspaper review stated30 ‘… it is a book the value of which will increase as time recedes, and which, in future ages, will be consulted by the physician and the historian’. The book also contains a series of interesting contemporary illustrations of life in Exeter.

The outbreak started in Sunderland in October 1831. Asiatic Cholera, as it was known, had been imported from the Baltic and quickly spread to the rest of the Great Britain.

In November 1831 a Board of Health planning committee had been set up in Exeter in preparation for an outbreak.

By mid-June cholera was being reported in Plymouth, a large coastal town fifty miles (eighty kilometres) to the west of Exeter.

Then ‘On the 19th of July the expected storm broke upon the City’. Shapter attended one of the first patients with one of the district surgeons, though it is not clear in what capacity. They called in Dr Blackall to confirm the diagnosis of cholera. Shapter then wrote to the Chairman of the Board of Health offering his services:

230, High-street, 20 July 1832

Sir

As there exist fears that the appearance of the malignant Cholera in the City may call into activity the duties of the Board of Health, I beg to state that my services may be commanded in any way that may be deemed of public advantage.

The Board having been constituted before I had taken up my residence in Exeter is the cause that I have not before proffered my assistance.

I am &c.,

Thos. Shapter, M.D.

Over the next three months more than a thousand persons in the city contracted cholera; 402 died of the disease.

His book describes the prevailing sanitary conditions and how the city responded. He painstakingly mapped the location of those affected. His map of the locations of cholera deaths in the city was the first instance of using a map to understand spread of this disease (Image 4).

Shapter’s research was acknowledged by Dr John Snow31 who mapped the incidence of the disease in Soho in 1854 and famously proposed that the disease was infectious. In 1839 Dr William Budd, whilst working at his father’s country practice in North Tawton, Devon, had used a map (sadly now lost) to show the spread of typhoid32 around that town.

Shapter described the clinical features of cholera and that mercury, externally or internally, was the most useful treatment, and that bleeding – by leeches or venesection – was useful in the early stages. He also gave several anecdotes about some of the patients, most of whom can be identified from the information he gives. It is not clear what his role as a clinician was during the outbreak; five of the city’s district surgeons, including Peter Hennis, but not Shapter, were specifically acknowledged for their efforts. Although Shapter is often portrayed as the hero of the epidemic in Exeter, this is probably an exaggeration.

He did not believe that cholera was an infectious disease and surmised that ‘… Cholera is essentially an epidemic, originating in, and chiefly due to, aerial influences, but capable, under peculiar and rare conditions, of being transmitted from man to man’ – a view he maintained in his 1866 sequel to this book titled ‘Sanitary measures and their results’.33 In this later book he showed that, after improvements to the drains, cleanliness in the streets and the water supply, Exeter was able to avert a serious epidemic when cholera was prevalent again in 1849.