Dr William Budd and The Typhoid Outbreak in mid-Devon 1839-40

William Budd was probably the most famous doctor to have been born in mid Devon. He is remembered mainly for showing, from scientific study, that Typhoid (or Enteric) Fever was a contagious disease, i.e. spread from one person to another. He also conducted research into the spread of Cholera and other infectious diseases.

The sixth child of Samuel and Catherine Budd, William was born in North Tawton in 1811.

His father, Samuel Budd, had been a surgeon in North Tawton from about 1796. Between 1827 and 1826, and again in 1836 he had been contracted by the Overseers of the Poor in Bow to treat their paupers as well. Samuel Budd married Catherine Wreford of Natson in Bow in 1801.

William did his medical training in Paris and Edinburgh, where he graduated MD in 1838. He was awarded a gold medal in that exam, for his thesis on rheumatism. Between then and 1841, when he set up practice in Bristol, he spent some time back home in North Tawton.

The Thackeray Prize, awarded by the Provincial Medical and Surgical Association - the forerunner of the BMA - was instituted in 1837 by Dr William Thackeray of Chester who donated most of the £50 prize money.

William Budd was one of the eight doctors who anonymously entered the competition.The winner's name was announced at the Association's Annual meeting held in Southampton on 22 July 1840.

The prize was won by a senior physician in Glasgow, Dr William Davidson (1799-1855). Budd's essay was awarded second place but the examiners were "also unanimously of opinion that [his] essay ... although not equal in all respects to the other, is a very valuable memoir; and had [the winning] essay not been presented we should have willingly awarded [it] the prize".

The essays were anonymous, although Davidson left a clue to his identity by refering to his records of patients admitted to Glasgow Fever Hospital. His essay - in which he proposed that Typhoid and Typhus were not separate diseases - was later published by one of the judges of the competition.

Although the Thackeray Prize had been announced two years earlier, it was probable that Budd only decided to enter the competition after the July 1839 outbreak had become established in North Tawton. His 189 page essay was finished on 27 December 1839, leaving him only four days to submit it. At the time of the essay competition, the prevailing view in Britain was that Typhoid and Typhus were the same disease, and that arose from rotting vegetation, sewerage etc. He ended his essay stating "... many of [my opinions] are, I well know, in direct opposition to opinions that have long been generally received, that have repeatedly been favoured in various countries..."

It was not until twenty years later that Budd's theory that they were separate diseases and spread from person to person gradually became accepted. It is ironic that the inhabitants of Morchard Bishop knew that the "North Tawton Fever" was contagious yet Budd was unable to convince the hospital physicians, who, whilst treating patients, were shielded from the epidemiology.

Budd's essay was returned to him and was believed to have been lost.

However Dale C Smith discovered the manuscript in the National Library of Medicine in Bethsada, Maryland USA, and published it in 1984. From this essay, and Budd's 1873 book on Typhoid Fever it is possible to identify some of the people in and around North Tawton that were involved in the outbreak.

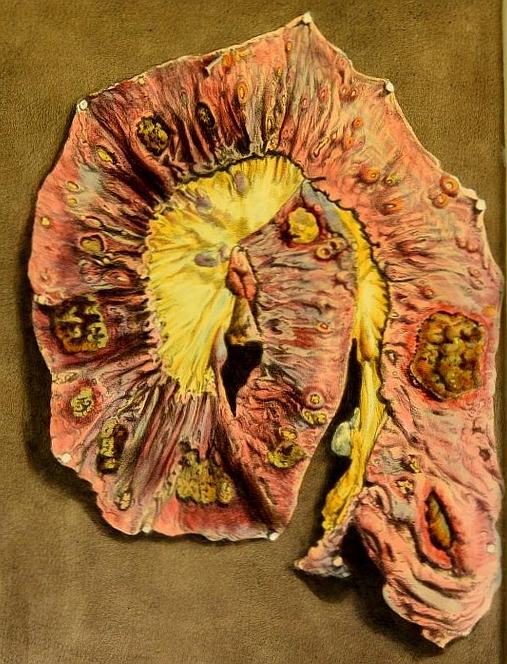

Right: Ilustration from William Budd's Book

"Typhoid Fever" published in 1873, depicting the "typical yellow typhoid matter" in the lower end of the ileum at day 17 in the illness.

On 11 July 1839, two girls developed Typhoid Fever in North Tawton. Within four months more than eighty inhabitants of the town had contracted the disease. Almost all were cared for by Dr William Budd.

He described how the disease attacked households. Ann Northam, 16, a wool carder, lived with her parents on the High Street. The daughter of an agricultural labourer, she was the first person in the village to be affected. Her mother Grace and two younger siblings subsequently contracted the disease; only her father John (who had had fever before) and youngest brother were unaffected.

Seven year old Mary Devenish lived at the bottom of Fore St but attended the girls’ school opposite the Northam’s. She was the second person to get ill. Neither girl had been out of the village for several months. Mary’s older sister Martha aged 9 was the next. (Their father Henry Devenish gave his occupation in the 1841 census as a sloper – a maker of overalls. Ten years later Henry, Mary and Martha were living in Exeter, all employed at Hitchcock, Maunder and Hitchcock’s woollen mill at Exwick.) One of William Budd's brothers, Thomas Septimus, then aged 22, also acquired the disease.

Three people from the village who had contracted the disease left North Tawton while they were unwell and infectious. Two were carpenters who returned to their homes in Morchard Bishop. Robert Cheriton, a married man of 41 with four children had been lodging in a house next to the school. He "began to droop" on 26 July, returned home on 2 August, and died of the disease three weeks later; his children contracted the disease but survived. The other carpenter, John Allen (28), also survived, but a friend who visited him whilst he was ill developed the disease, and passed it on to two of his children and his brother. In Morchard Bishop the illness was known as “North Tawton Fever”.

The third person who left North Tawton whilst ill was a widow named Lee. She had been born Mary Snell in Zeal Monachorum in 1787. The daughter of Andrew Snell (a relative of Budd's mother) and Betty (nee Easterbrook) of Loosebeare, she had married John Lee in Zeal in 1813. In August 1839, shortly after becoming ill, she visited her brother John who farmed at Chaffcombe, between Down St Mary and Copplestone. (John Snell was 45. In June that year he had married Sarah, the 20 year old daughter of Thomas and Sarah Moon, farmers of Chaffcombe.)

Whilst Mary Lee was at her brother’s, all the symptoms and signs of typhoid developed, but, under Dr Budd’s care, she slowly recovered. At that time, he had seventeen other patients ill with typhoid in North Tawton. But as she started to improve, her brother’s wife Sarah, who had nursed her, became seriously ill and died on 4 November. John Snell who had cared for his late wife then contracted the disease and took to his bed on the day his wife died. He survived, but four farm workers and two women went down with it. One was Mrs Lee’s daughter Fanny aged 18 who had acted as a nurse. The other, Mary Gibbings, a servant aged 31, was sent to her home to the hamlet of Loosebeare where she slowly recovered, but not before her father John, a farm labourer, and a neighbour, Mr Kelland were taken ill with the same disease.

The fifth person of the ten who contracted the fever at Chaffcombe was Oliver Lang, a farm worker aged about 14. He too was sent home, to Stone Farm, between Bow and North Tawton, where his father John was an agricultural labourer. He became seriously ill, but survived. His mother, Joanne, who was nursing him, then acquired the infection, as did his two sisters, one of whom, Mary, died from typhoid on 2 February 1840 aged 22.

(After his wife Sarah died, John Snell remarried 13 months later to Mary Ann Searles of Down St Mary, but 16 months later she too died. John married (for the third time in two years) just six days after her funeral, to Mary Daw in Colebrooke Church. They then farmed at Edgerley, near Lapford for many years until he died in his late seventies.)

Dr William Budd married Caroline Hilton in Bath in 1847. They had 9 children. They lived in Bristol until his death in 1880.

Half way though the Typhoid Epidemic, Dr William Budd was called out in the middle of the night...

On 2nd January 1840, at just after one o’clock in the morning, he was summoned to attend Richard Bolt, an agricultural apprentice aged 17, at John Webber's house at Week, a hamlet just outside North Tawton near the Taw bridge. Bolt and his friend and neighbour Thomas Nosworthy (19) had had a few beers at Ash’s (White Hart) in Fore St, North Tawton and then had had an argument. On their way home, Nosworthy had stabbed Bolt in the left side of his neck with a pocket knife. The wound was quite deep and the blade had severed the external carotid artery and some nerves. He was bleeding profusely.

With his father's assistance, and by candle light, Budd tied off the artery and closed the wound. The wound healed well but with the left side of his tongue paralysed the patient had difficulty in swallowing. Budd speculated as to which nerves might have been severed. He wrote a letter to his older brother Richard, describing the injury, claiming that no post mortem would be likely as “unfortunately for science and for myself, my patient will not die.” He was mistaken. On 22 March the lad died in his home. Budd did a post-mortem and stated later that death was caused by lung inflammation as a result of swallowing difficulties allowing food and drink to “go down the wrong way” (aspiration pneumonia).

The inquest into Richard Bolt’s death was held on 23 March at Week and lasted from 1pm until 11pm. Nosworthy, who had been remanded in Exeter jail since the day of the stabbing, was found guilty of manslaughter and sent for trial at the assizes.

On 30 July he was tried for murder at Exeter Lammas Assize. His defence produced various character references and a dying deposition from Bolt, forgiving his assailant. Found guilty of manslaughter, he was sentenced to one year’s imprisonment with hard labour.

by Peter Selley